I’ve been co-organising Deliver Sessions meetup in Manchester for a while, and this year I’ve been writing some notes after each one so I can look back. In November 2023, we were hosted at Michael Page’s office in Spinningfields, where we played a fun interactive game from Mark Kirschstein that had lots of insights into the troubles coordinating teams can cause even when everyone’s trying their best.

This game was a version of the “MIT Sloan Beer Game”, which was invented in 1960. I should warn you now, there’s several ways you might get a chance to play this, and it’s much more interesting if you go into it with no spoilers! I learned loads from trying it out at the meetup while trying to guess some bigger-picture things that were going on, and found Mark’s walkthrough and discussion at the end really eye-opening.

So this blog post’s divided into 2 parts:

- A few pointers on how you and a group (your team at work?) could get a chance to try this out, with as little up-front info as possible

- Some things I learned from doing this game, and why I found it so interesting (minor spoilers!)

How you might get a chance to try this game out

Getting to play this game with as little pre-reading as possible is brilliant. The rules are simple and ideas for doing well at it seem fairly obvious… so it’s good to jump in, see how it goes, and review afterwards why you took certain actions and why things didn’t work out as well as you expected.

The game was created by Jay Wright Forrester at the MIT Sloan School of Management in 1960, and is such a good way to help people experience some system dynamics topics that it’s still being used there. It’s also got versions (often using the exact same rules) offered by various places and people online.

The game takes about an hour, and splits participants up to manage different stations in a supply chain. They work together to meet customer orders. This can be done using paper order slips and plastic tokens moving round stations, or using an online tool – at the meetup, we needed one smartphone for each station, using a website Mark made so we could see info and send instructions.

You can play it with small or large groups (from 4 people up to as many as you can handle). To get the most out of it, you’ll want a facilitator who knows the game, so they can explain the rules, guide participants through the first steps until they get the hang of it, and lead a “what happened?” discussion after the game ends.

Who could you get to facilitate? Mark did this role expertly at the meetup, and has done it internally at companies where he’s worked as a coach/trainer before – maybe you can find him or someone similarly qualified? Or, is this something you could learn? Or maybe ask some keen person you work with to learn, so you get to participate? I’ve found a few links to help get started – haven’t tried using these myself, but they look promising:

- A guide to setting up and running the physical version (with markers and flipcharts).

- A free online version you can use (including by yourself, with bots running the other stations so you can practice), with a step-by-step walkthrough to help understand it.

- Another site has a digital version that looks too old to run, but there is a nice debriefing guide you can use to help people get the most out of the post-game discussion.

Some things I learned (minor spoilers!)

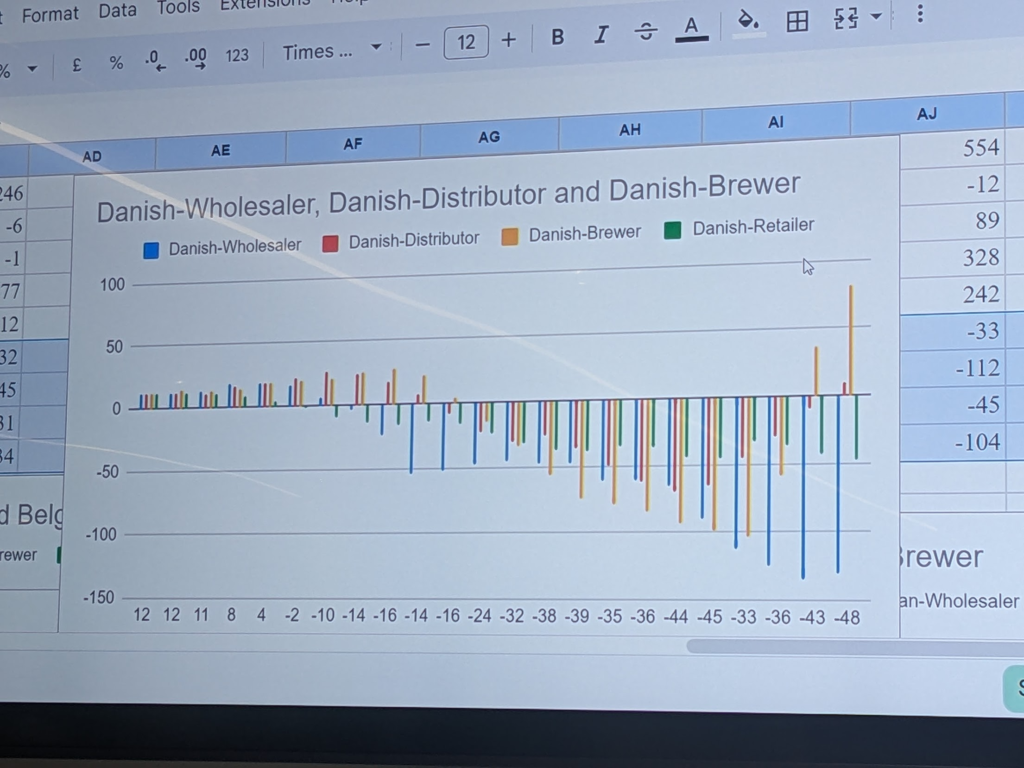

Considering how few rules and decision points the game had, and how much everyone was trying to achieve the same outcome (minimize total costs for our supply chain as a whole), we all did a horrible job. Every supply chain’s excess inventory and back orders were all over the place, swinging wildly around. I think my team’s was the worst, but everyone’s was chaotic.

Talking through what the causes of this might be, Mark asked if it felt like it was anyone else’s fault. That’s definitely a strong natural impulse – if this is simple to get right and I feel I’m doing the right thing, someone else must be messing up, right? For this game, we knew we’d all just been given different roles at random – think about how much stronger this impulse would be in a real scenario, dealing with “them” (a different department, or a third party, with unknown processes, different incentives, levels of competence…)

We also strongly suspected that varying market demand was the hard thing to deal with. It was a shock to see what the actual week-by-week demand getting fed into the system was — through long periods of it being absolutely static, all stations in the chains were doing all kinds of unpredictable actions, responding to fluctuations we were causing for ourselves and making worse with no external help.

We talked about what might have helped: ideas such as meetings (”What are your numbers, what’s your plan for next steps”) or access to see what all the stations were seeing should help, but would certainly cause a fair bit of overhead. Apparently, the simplest, fastest way to make everything run smoothly would be to just show every station what the end customer’s actually asking for. With access to that, lots of the other issues sort themselves out.

Without seeing the overall “What need are we actually all trying to meet”, it’s much like at most big companies: every team / individual tries to work out what their internal “customers” want, make up all kinds of complicated stories, second guess and blame each other, and dream up all kinds of overhead and ceremony to try coordinating better. I’ve heard and seen lots of this kind of thing before – but experiencing it, seeing how hard it is to get things working well in a very simple scenario, was fascinating.

The session’s inspired me to do more reading about what others have concluded from the game. It’s been around for over 60 years so there’s been plenty of time for reflection.

From MIT News’ “The secrets of the system”:

- “CEOs of Fortune 50 companies do no better [at the game] than high school students”

- “teams whose members are allowed to communicate with each other perform no better than other teams”

- Everyone jumps to the same answers our discussion started with … and it doesn’t help!

- “We have a strong tendency toward blaming people for the performance of the system they are in”, and discusses the fundamental attribution error.

- I looked into this and related errors after Annette Joseph’s Agile Manchester keynote, it’s important to know how easily we’re drawn to blaming people and groups for things they just aren’t doing.

A paper from the Sloan School of Management, “Teaching takes off: Flight simulators for management education” gives lots of economics and management terms you can use to find related topics:

- “The patterns of behavior observed in the game – oscillation, amplification, and phase lag – are readily apparent in the real economy”

- Pointing to long-term cycles of boom and bust, individual companies’ issues, and reasons behind panic buying.

- “By blaming outside forces we deny ourselves the opportunity to learn – recall that nearly all players conclude their roller coaster ride was caused by fluctuating demand. Focusing on external events leads people to seek better forecasts rather than redesigning the system to be robust in the face of the inevitable forecast errors.”

- I love this take: we can easily take the wrong lessons from our experience, and put more and more effort into solutions that just aren’t going to help.

More Deliver Sessions

Deliver Sessions will be back in 2024 – follow the meetup to get emailed when new dates get booked. And if you’re at all tempted to present something yourself, you can have a look at some past notes for inspiration: we’re bound to do another evening of lightning talks, some workshops, and some longer talk / Q+A sessions. Get in touch with me or another organiser and let us know what you’re thinking.

Comments

2 responses to “Deliver Sessions: “Why did that take so long?””

This is really insightful. I have never tried the game and some of your observations are surprising. The collection of conclusions is interesting to say the least. Thank you so much for this article.

That’s brilliant to hear, glad you found this useful! Thanks for sharing your thoughts.