I’ve used this technique for several years since learning about it from Dr Sal Freudenberg – thank you Sal! The illustration above is from a “Taming Unicorns with Technology” workshop I ran with Katie Roberts, where we described how using this rather than MoSCoW or other techniques helped hugely with discussions and decision making.

Using the lines

Looking at some time period (end of a project, a quarter, what’s done for a big launch date), you can build an ordered list of all the work you’d like to do. Discuss and agree the items with team members, stakeholders, and anyone you’d usually involve in this kind of thing.

We’re not putting things in a single list because we’re going to work through things one at a time. That’s one option, but maybe you’ve got multiple pairs or teams you can divide it up amongst in parallel. This ordering activity is separate from scheduling.

The question to start with it: If we have a horrible time of it – complications everywhere, folk off sick, etc. etc. – and we only manage to come out with one thing, just one thing, what would you like it to be?

And if we got two? Work on down the list. And have a think for various pairs of items. If we really only got this far, and didn’t do that one – would you be sorry? Would you rather we switch these?

Repeat as you do this: I’m not saying you won’t get things, or that we’re only working in this order. It’s just about choices we’ll make if it comes to it.

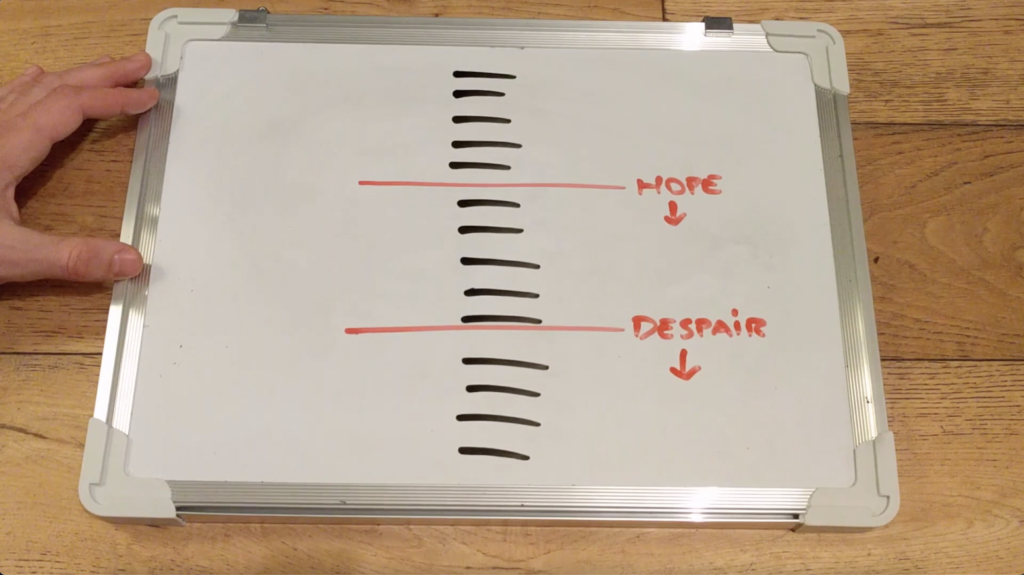

Then, using your best judgement and whatever data you have (you can go away and have a good think and planning around this), put 2 lines against the list.

First, the line of hope: from the top of the list down to this line, you’re very confident you’ll get it all done by the deadline. It’d have to be a real set of surprises for you to not get all that.

Below this line, we can hope to get things – we might get into this section of the list, but it’s uncertain. And the further below the line you go, the less likely an item becomes.

Does that make anyone want to move things? See something a bit below the line you’d really like to be in the top section? Might not be able to swap 1 for 1, excellent area for discussion.

Then, add the line of despair: lower down, there’s a line meaning we’re spectacularly unlikely to get things below this done. Does that make us want to move anything around to get it on the other side of that line?

If the lines are close together, it’s a sign that we’ve got a lot of confidence in what the work is and our capacity to get through it. Further apart shows we’re not that sure.

This is useful – you can review and move the lines around as you see how fast the first few things go. Typically, they’d start quite widely apart and move towards each other. But if they don’t, it’s a clear visualisation of how things are staying uncertain.

It’s great to have some kind of language about this, it removes lots of stress. Sometimes people think if you can’t give precision answers you can’t know anything. We all need to be comfortable with uncertainty.

An example of things this approach helps with

I found this extremely useful when I had a large team divided into a few squads, but lots of options for swarming on things or putting effort into persuading other people and teams to support us if needed. If something’s near the top we know where to put that effort in.

When unexpected problems came up, it was pretty simple to think about and communicate how that affected these lines (and whether anyone now wanted to move priorities). Much easier than big Tetris games trying to work out where to move people and when individual items will slot in.

When a new important thing appeared, it was really easy to talk about “what’s this more important than”. I had a “must do” panic appear mid-quarter once, and could quickly run through the same “what would you wish we’d done by the deadline” discussion. This meant we had clear choices (we’re not taking everyone off x for this, because that’s still higher on the list, but we can park work on these other things if it helps ensure the new item gets done).