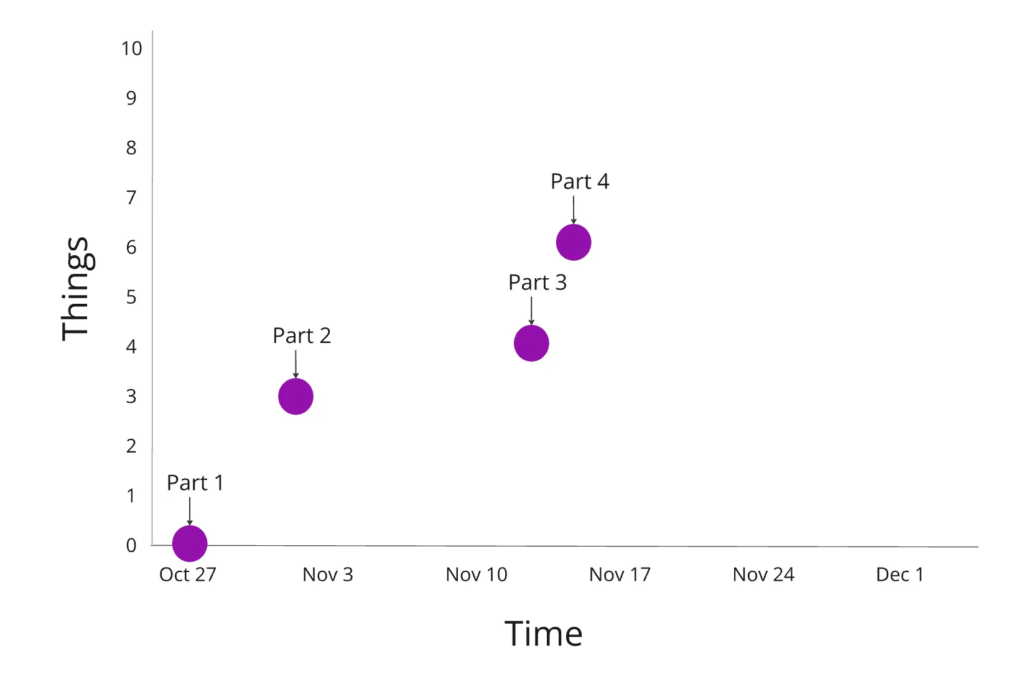

We’ve covered several things about OKRs already:

- part 1 introduced this series

- part 2 described the OKR origin story

- part 3 looked at what else was going on while some companies used OKRs.

Today, in part 4, we’ll look at a few things it took me quite a while to realise.

It’s easy to get excited about the promise of OKRs: aim for outrageous success, and if you get anywhere close to it you’ll still have got much further than you expected. This is often combined with the idea that every team should have an OKR (at least one).

But remember what makes “stretching” work, in the examples we’ve seen so far. In part 3, Google was solving problems in ways nobody had ever thought of – and had the scope and permission to try out all kinds of ideas, like running the site with corkboard computers and finding loopholes in data centre agreements. And that idea from part 2 – about the rest of the company being ready to jump in and help as soon as they realised a way to support the main objective – is present in lots of examples in John Doerr’s book.

Does that sound like the way you’ve seen teams setup to stretch? More often, I’ve seen every team with their set people, budget and processes, with their own stretch goals to focus on, and none of this ability to put extra effort into anything else.

It was some time before I understood the important distinction between two types of OKR you can use.

Lots of companies make a clear distinction between:

- Aspirational – the ambitious, never-expect-to-reach-it, stretching-and-getting-somewhere-near-it-would-be-amazing OKRs that get talked about a lot

- Committed – we really expect to achieve these results, and can make plans around meeting them.

Introducing this language means you can use OKRs both for new ideas and ambitions, where you’re not sure what’s possible but getting anywhere near to some number would be great, and for more concrete, important to hit measures. Once I’d spotted this once, I realised that it does get mentioned in lots of places – in Measure What Matters, inside Google, by Christina Wodtke – but I’d missed it.

As well as making some OKRs “results you can plan for”, I think there’s potential for letting some teams stretch (and get the help needed when they ask for it), while others can focus on important but not incredibly stretching work.

In addition to making some OKRs not stretching, do you know what else helps? Have fewer OKRs altogether.

At one point when I was worrying about having far too many OKRs around, a favourite choice for my kids’ bedtime story was “Angelica Sprocket’s pockets” by Quentin Blake. It starts: “Angelica Sprocket lives next door. Her overcoat has pockets galore.”, and has page after page of things – pockets for ducks, for boats, for straw hats for goats, and more. Reading through we wondered how do all these things fit in there? And why pack them all in to begin with?

That same feeling described what I see with OKRs sometimes, when people decide they’re too useful. Each team should have some OKRs about their product, and maybe some about improving their team, too. And individuals can have OKRs for their own performance – some about helping their team, and some about personal development. And communities of practice! They could use them, to describe what’s important for the roles in that community, each could have a few!

In one team, with maybe up to 14 people, how many different OKRs does that add up to? And how many directions is the team “radically focused” in? To quote the Angelica Sprocket book: “there’s more and more, and more, and more… Angelica Sprocket has pockets galore!”

Choose to use fewer aspirational OKRs, and fewer OKRs overall. You’ll achieve more.

An area where lots of people lose lots of time: picking the “right” measures for key results. How do we quantify the outcomes we want? And what measures can we influence, and get regular updates on? And will changing those numbers necessarily lead to the result we want?

One reassuring answer: you can never get this right. So, it’s fine to settle for measures that you know aren’t perfect – especially if that means you can quickly move on to doing the real work.

Write the story of what change the team wants to achieve — then pick your best guess at numbers you hope would indicate that change is coming true. Book in when you’ll reflect on what the numbers changed to, whether that’s lead to the story coming true, and what you’ve learned.

Using examples to illustrate Goodhart’s law help, talk about those a lot (I’ve written some advice in this post about DORA metrics). Helps remember there are no numbers that’ll perfectly describe what we want, only our best assumptions.

And never, never base people’s bonuses or ratings on those numbers being met.

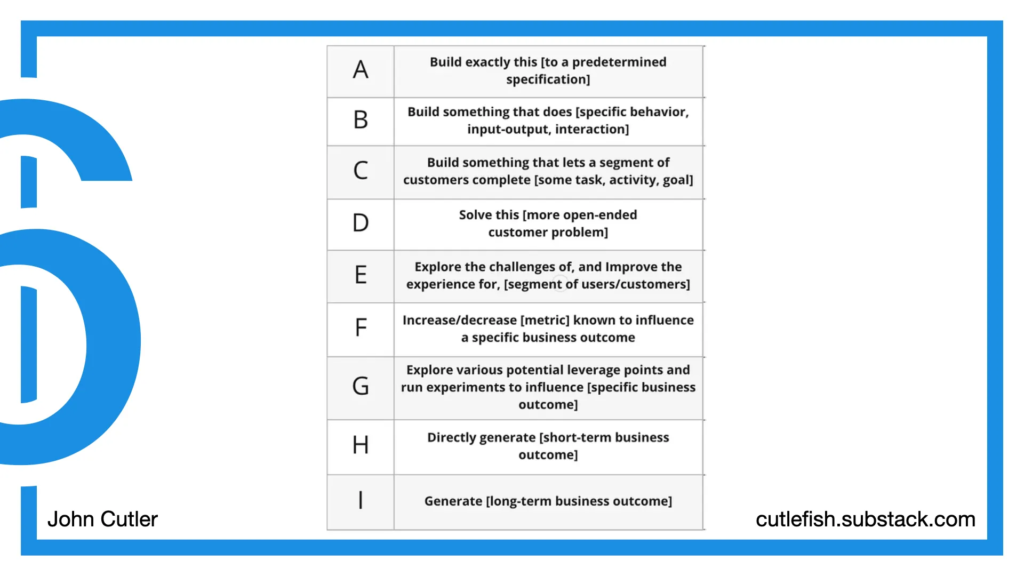

Another way we get caught up trying to pick the “right” measures is in looking for those big-picture, outcome-focused, business-impact measures that we know are important to focus on. The issue, for lots of teams, is that they don’t feel they’re in a position to influence those. I’ve found John Cutler’s mandate levels extremely helpful for having conversations about this. Sometimes, it feels like there’s only two choices: the team decides everything, or else “they” (the business, the exec, leadership) decide everything. These mandate levels give a more nuanced list of alternatives.

You can use these to start with data: looking at past initiatives over time, what level was the team operating in? Discussing this is useful, both to spot disagreement and misunderstanding, and to realise how often a team does get more autonomy (sometimes it feels like everything gets dictated, but data might show that’s just a few annoying examples looming large in the team’s memory). And once you know what’s been going on, you can discuss what to do about it.

- There’s work that needs to be done at all these levels – none of it’s unimportant or “lesser”.

- If a team can’t decide/influence at some level, it’s really not fair to expect them to craft OKRs pretending they can.

- It takes skill and experience to work at different levels – it can be more useful to agree to try out a different level for some new thing, and get support and discussion with it, rather than insist on jumping right in.

- Tracking and discussing these over time can be helpful: if it’s agreed that the team will practice operating at a different level, but again and again get given a “just this time” prescription, you can highlight the agreement and how reality’s moving away from it.

Making progress

This blog series is still short of that all-important, arbitrary, 70% success mark – but it’s mid-November and we are making good progress. Thing number 7, coming soon!

Update: It took a bit longer than I’d expected… but part 5 appeared on the very last day of the quarter, hitting that arbitrary “7 out of 10 is success” landmark just in time.